Net Neutrality May Have Slowed Down the Internet

Amid much hue and cry, apocalyptic predictions, and advocacy from “comedian” John Oliver’s HBO show, the FCC revoked the Open Internet Order in 2017 (effective 2018). Widely promoted as “Net Neutrality,” the policy had been adopted by the FCC in 2014 after public pressure by then-President Obama, and took effect in 2015. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now fairly assess how this policy fared and whether it was necessary to begin with.

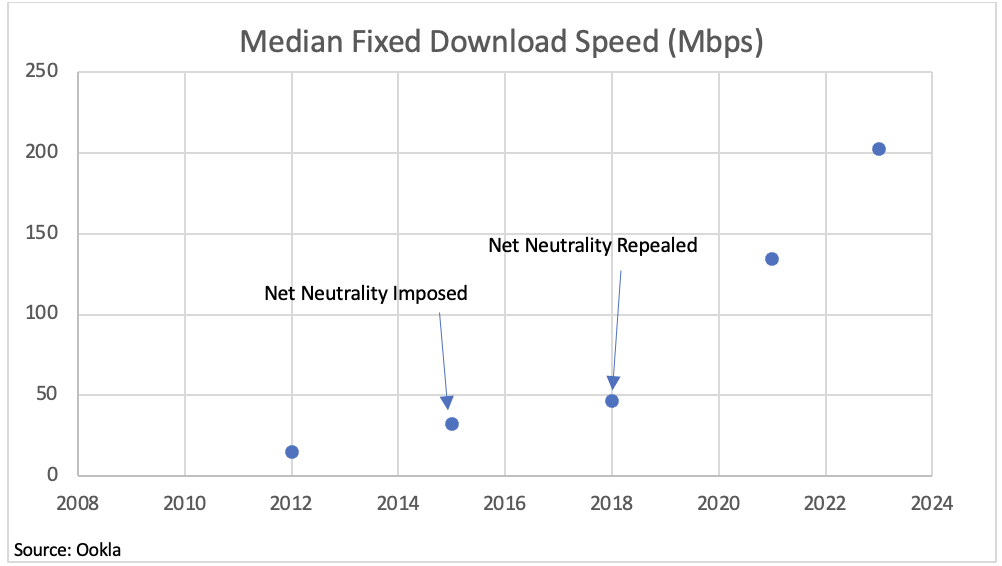

More precisely, we can compare the three years that Net Neutrality was in effect (2015-2018) to the three years before it was implemented (2012-2015) and the three years after it was repealed (2018-2021). In each case, the policy changes occurred roughly halfway through the calendar year. Former FCC Chair Ajit Pai recently defended the repeal by citing a 287% increase in average fixed broadband download speeds and a 570% increase in average mobile download speeds between the June 2018 repeal and today, according to speed tester Ookla.

While impressive, these figures represent the mean, which can be skewed by outliers, not the median, which more accurately reflects consumer experience. The mean is usually a good measure of average experience if the data set is relatively clustered around it, but this is not the case with broadband internet as some areas enjoy lightning-fast download speeds and some areas have no internet at all. We should therefore consider the median to control for these outliers.

Using the same source, the speed tester Ookla, we see that the median download speed for fixed broadband only increased a measly 190% in the three years after repeal, from just under 50 Mbps to close to 150 Mbps. By contrast, speeds increased 44% in the three years Net Neutrality was in effect. This was about the same as the rate of increase in the three years before this policy was enacted. Net Neutrality did nothing to improve download speeds and may have held back improvements.

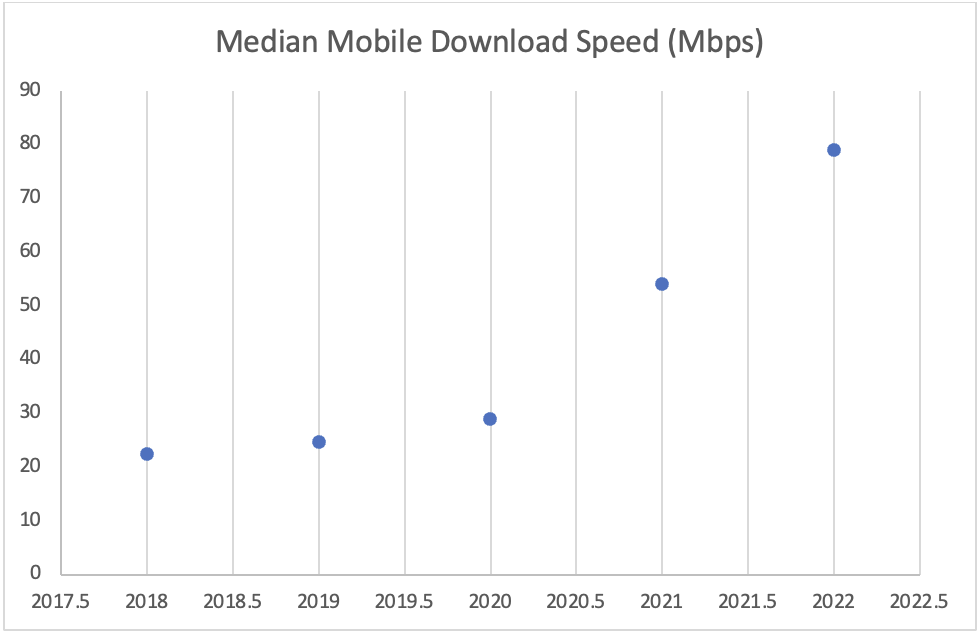

As for mobile, the technology was too new when Net Neutrality was first debated to have a meaningful comparison. However, we can see that the median mobile download speeds increased more than 250% since repeal, again using data from Ookla.

With these figures in mind, it is difficult to conclude that Net Neutrality was necessary to preserve internet access or innovation. Consumers who were warned that their Netflix would be throttled are enjoying faster internet than ever, and no “tiers” or “express lanes” have been created by ISPs. Net Neutrality was always a solution in search of a problem, had no positive effect on service, and arguably held improvements back. It is time to admit that this policy is an anachronistic relic that ought to be consigned to the ash-heap of History.