Biden FCC’s Digital Discrimination Order is Overbroad and Unworkable

By James Erwin

One to 218. No, that’s not the teacher-to-student ratio in Mumbai elementary schools (that would be a measly 1:36). That’s the number of pages in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorizing the FCC to embark on its digital discrimination rulemaking to the number of pages in the resulting Report and Order, which will be voted on at the Commission’s November 15 meeting. It would be comical if the product were not also dangerously overbroad and frustratingly unworkable.

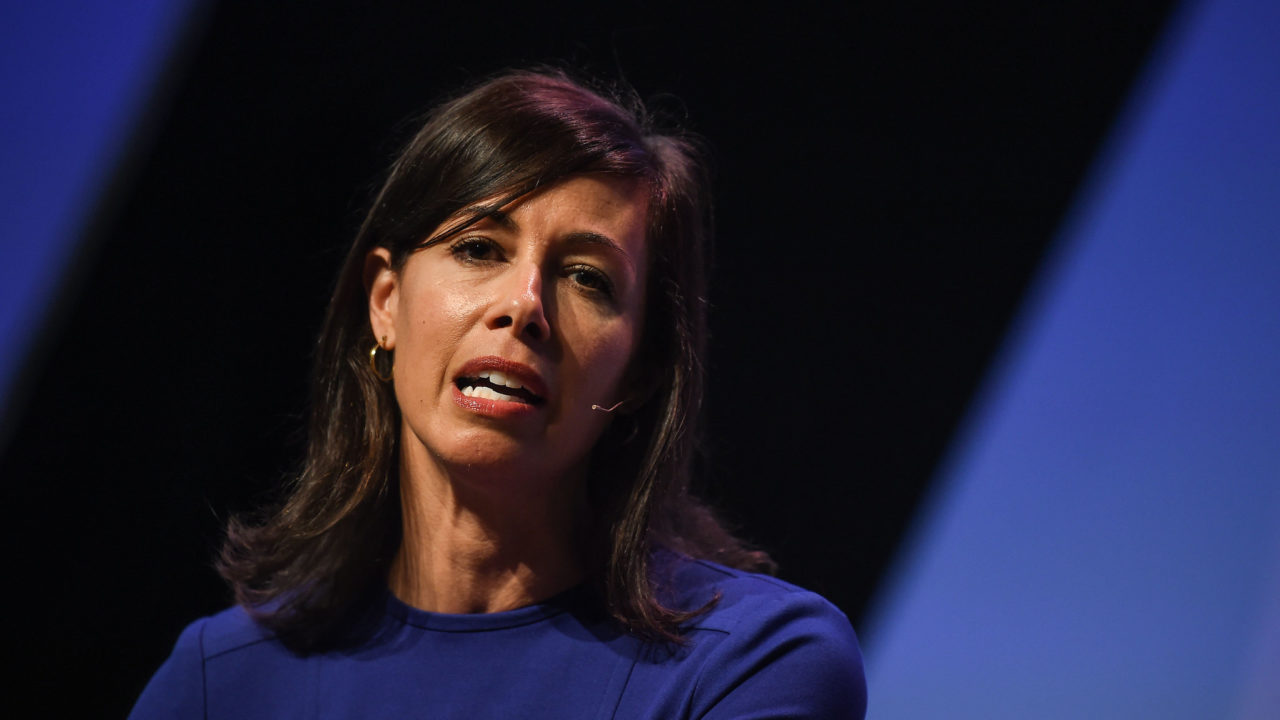

Tasked by a one-page section of the IIJA with defining digital discrimination and identifying best practices to prevent and eliminate it, Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel’s team managed to wring more pages of regulations out of this remit than there are Democrats in the House of Representatives. This is an especially impressive feat given that, as Commissioner Brendan Carr noted, “After nearly two years and several rounds of comments, the FCC’s draft order concludes that ‘there is little or no evidence’ in the agency’s record to even indicate that there has been any intentional discrimination in the broadband market within the meaning of the statute.”

To be fair, much of a report and order consists of the report section, which explains the findings of the FCC to justify the regulations issued in the accompanying order. Even bearing that in mind, however, one realizes that the FCC was unable to prove in 218 pages that “digital discrimination” – which again, they get to define – was happening in the first place, yet nonetheless imposed significant new liabilities on the private sector.

What liabilities exactly? Contrary to the recommendations submitted by Digital Liberty in multiple filings, the FCC has opted to adopt the disparate impact over the disparate treatment standard. Essentially, the FCC is trying to grant itself the power to take telecommunications service providers to court for discrimination if they do not serve customers in exactly the same manner regardless of income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin. The FCC would be able to shake down any telco that has any discrepancy in service between black and white customers, Hispanic and non-Hispanic customers, immigrant and native-born, and even rich and poor. Someone who can’t afford to pay for service from a private company must be treated the same as someone who can. Presumably, this would apply to the treatment Catholic vs Protestant customers as well?

The alternative advocated by Digital Liberty was to follow the precedent of almost all civil rights law and require actual proof of discrimination before anyone can be held liable. One begins to wonder if they elected to go a different route, presuming discriminatory intent if there is any difference between these groups, because they worried that they would not find any proof. As Commission Carr attests, they haven’t found any yet. These companies, after all, are competing for the most customers and have zero interest in saying no to any customer who can pay.

Additionally, the text of the order specifically empowers the FCC, for the first time, to regulate every single internet service provider’s:

- “network infrastructure deployment, network reliability, network upgrades, network maintenance, customer-premises equipment, and installation”;

- “speeds, capacities, latency, data caps, throttling, pricing, promotional rates, imposition of late fees, opportunity for equipment rental, installation time, contract renewal terms, service termination terms, and use of customer credit and account history”;

- “mandatory arbitration clauses, pricing, deposits, discounts, customer service, language options, credit checks, marketing or advertising, contract renewal, upgrades, account termination, transfers to another covered entity, and service suspension.”

This is a substantial overreach by the Biden FCC for multiple reasons. First, the page ratio matters. The Supreme Court has grown increasingly skeptical in the last few years of agencies reading dubiously broad mandates for themselves into short statutes. One page of Congressional authorization yielding 218 pages of enforceable law should raise eyebrows on its own, especially since the one was written by elected representatives and the 218 by unelected bureaucrats. What makes this even worse is that Congress clearly did not intend for one page of an infrastructure bill to be used as justification to overhaul civil rights law in a manner inconsistent with recent legal precedent.

Second, the bulleted list above demonstrates the degree of micromanagement the FCC can get up to under this regime. It is a regime of central planning that even Khrushchev would have done away with during his de-Stalinization reforms in the late 50s. Good Soviets that they are, the FCC staff have also made sure to trap every company in the industry in a Catch-22: the Commission is empowered to regulate “actions and omissions, whether recurring or a single instance.” If you build too much in one area, you’re guilty. If you build not enough in another, you’re guilty. If this is a systemic business practice, you’re guilty. If this happened once long ago due to a decision someone who no longer works with you made, you’re guilty. There’s really no way out.

But don’t worry! We still have due process in this country. Every covered entity is permitted to provide the FCC with an explanation as to why they made the decisions they did, and they are generously granted this opportunity before they ever need appear in court. This is where we get to the unworkability of the order. Technically, companies can dispute scurrilous accusations of racism from DC bureaucrats when the only color they care about is green. In practice, the FCC will hang like the Sword of Damocles over every decision they make. There is no way the FCC has the time or resources to litigate that many actions by that many disconnected people, so whatever rules are in place will go unenforced.

At the same time, the fear of arbitrary lawsuits by the federal government will chill investment and discourage deployment to unserved areas. The entire purpose of the broadband portion of the infrastructure bill was to close the digital divide by providing over $40 billion to subsidize deployment. In Rosenworcel’s mind, Congress authorized $42.5 billion to close the digital divide but also wanted to make sure no rational actor would participate in the program for fear of discrimination suits.

While there may be legal challenges ahead for this order, it is likely to be adopted by the FCC at its meeting next week. Regardless, we at Digital Liberty once again implore the Commission to choose a different path.